Stanford Wager – bet on yourself

A social experiment in dopamine, money, and trust in games

Wager started as a class project in Stanford’s ENG145 Technology Entrepreneurship course and quickly turned into something more uncomfortable:

a real-money wagering platform for Gen Z gamers, built by people (including me) who care a lot about responsible technology.

That tension is the whole point of why this project belongs on my portfolio.

I wanted to understand, from the inside, why products that play directly with dopamine, money, and status are so powerful and where the line is between “fun” and “exploitative.”

TL;DR

- Built a peer-to-peer wagering platform where players bet on their own performance in games like Clash Royale; the platform takes a small cut per match.

- Soft-launched at Stanford: 30+ users within ~1 hour, $80+ wagered in a single evening with just one day of marketing.

- Secured a €100k investment offer from Sukna Ventures and later spun the venture out to Antler NYC, where it’s now being rebuilt and run by Jack Mascone.

- For me, Wager became a values stress-test: can you design a betting product that’s transparent, skill-based, and less harmful or is the entire category fundamentally misaligned with the kind of systems I want to spend my life building?

Turn on sound to see the product in action:

1. The origin story: a €10 bet that no one paid

During Euro 2024, on day one at Stanford, my friend Tom and I (very German about football) made a €10 bet on Switzerland vs Germany. Tom had an exchange semester previously in St. Gallen and showed up with a Switzerland jersey. Unacceptable haha.

Switzerland lost.

Then we played a FIFA rematch.

Then nobody paid.

On the same day, at a Berkeley hackathon final, Tom pitched a thought he’d been carrying for years:

“What if there was an app that made these casual bets actually stick?”

The idea was simple enough to explain in one sentence:

A platform that lets gamers of all skill levels bet real money on themselves in their favorite multiplayer games.

Our class at Stanford’s ENG145 required us to turn a raw idea into a fundable startup in eight weeks. Wager became our case study.

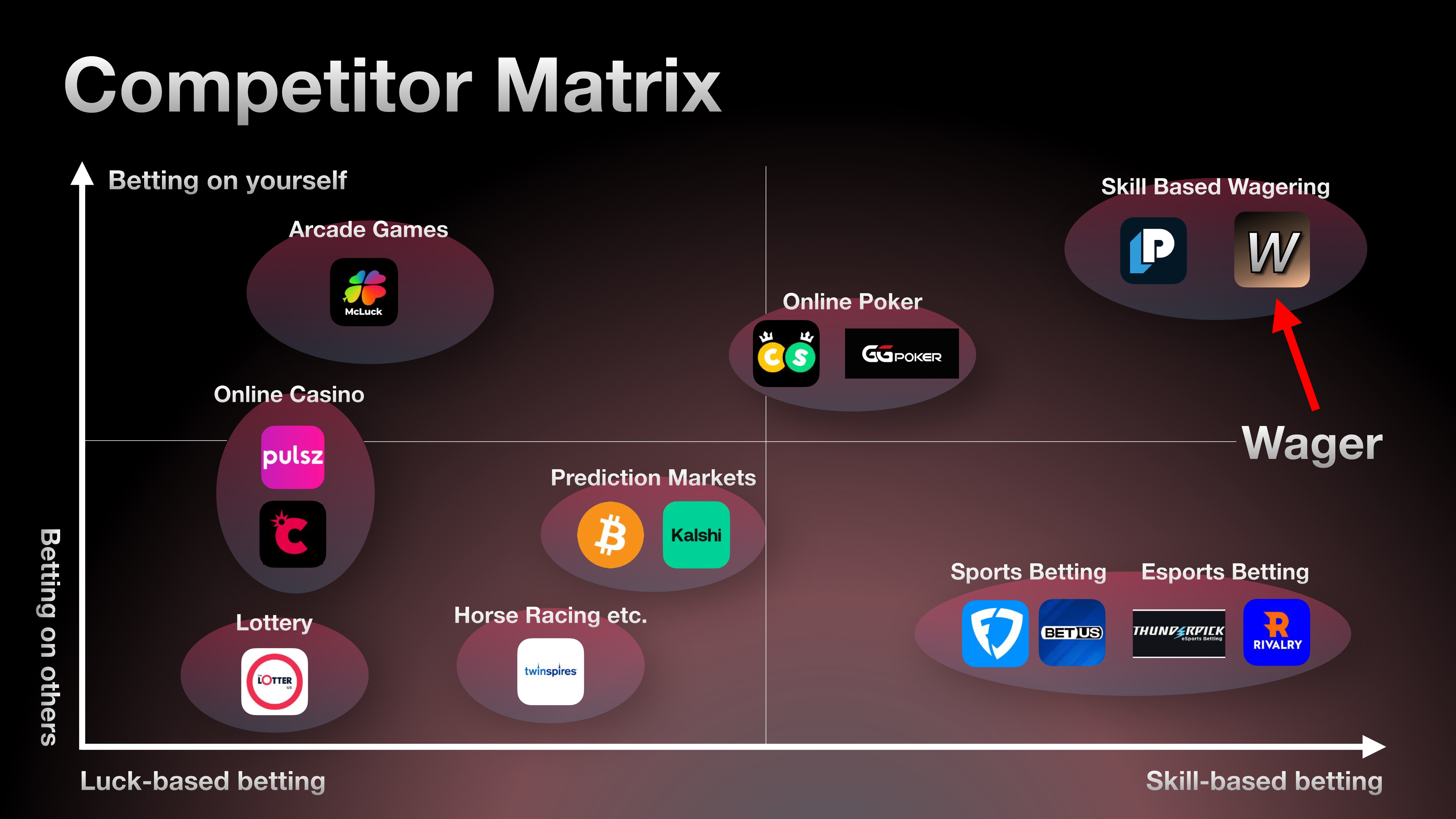

2. The market we stepped into

We started with a few uncomfortable facts:

- The esports market is around $3B in 2024, growing at ~27% CAGR from 2023-2030.

- The first-ever Esports Olympics in 2025 will bring millions of new viewers into competitive gaming.

- Our competitors, like Players’ Lounge (YC W18), have already processed $200M+ in wagers.

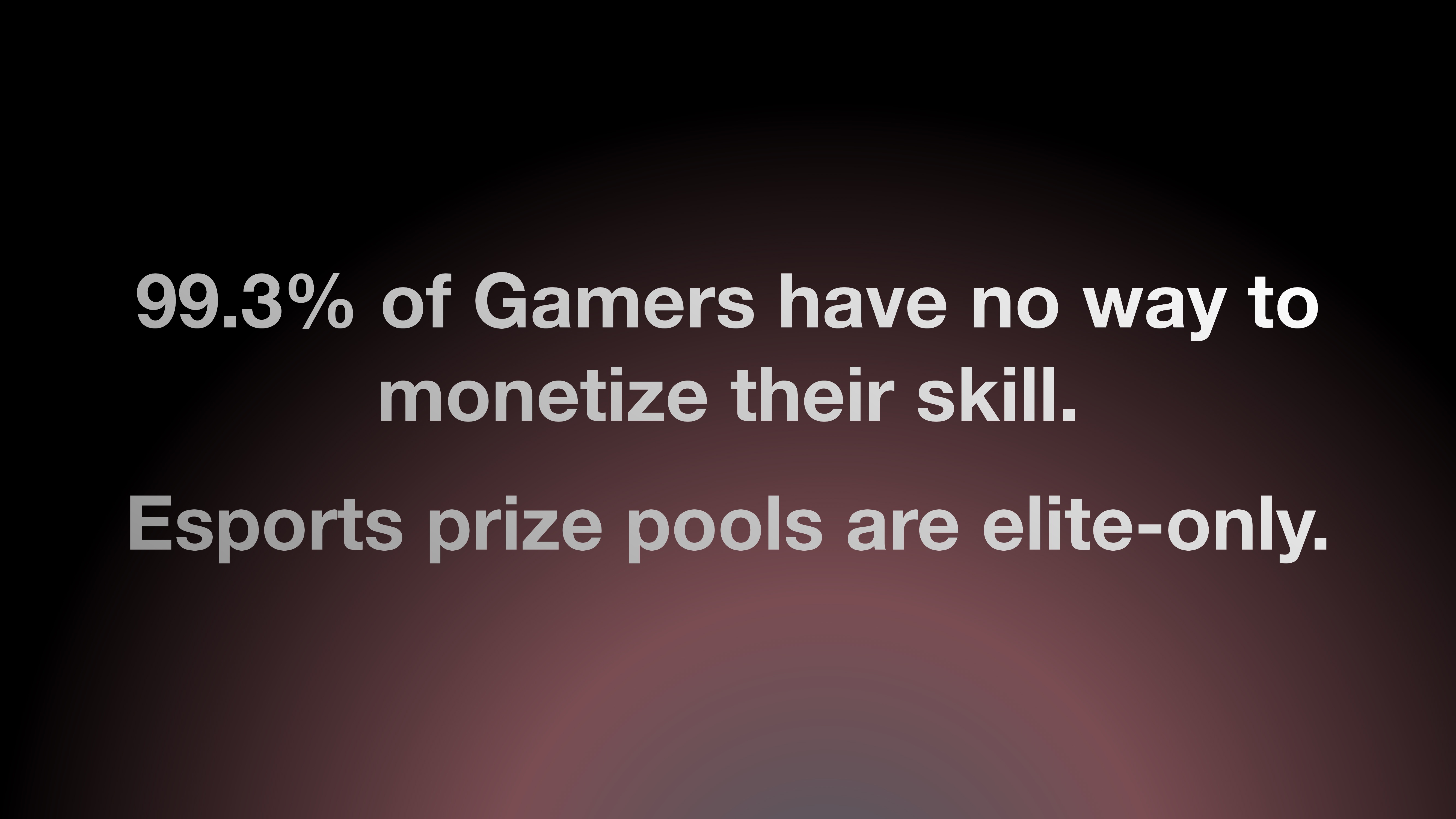

At the same time, almost none of the people we know are good enough to win big tournaments. They’re the 99.3% of gamers who are competitive, but not pro.

We framed Wager as:

“Online poker for video games” : you bet on your own skill, not on some distant team you’ve never met.

And yes, the business model is brutally simple:

We take ~10% commission on each peer-to-peer wager. High-frequency, small-stake bets can add up to serious revenue.

3. Why this is the opposite of how I say I want to build

I usually talk about:

- Building products that age well, not just farm attention.

- Avoiding manipulative mechanics that exploit addictions.

- Designing for trust, agency, and long-term value.

So why on earth build a wagering platform?

Because it forces three hard questions:

-

Is all betting inherently harmful, or does context matter?

We chose skill-based, 1:1 wagers where you only bet on yourself, not on others or pure chance. That’s still risky but structurally very different from slots or loot boxes. -

Can product design reduce harm in a space that’s structurally addictive?

We experimented with stake limits, loss caps, and transparent flows from the very first prototype. -

Do my values hold up when there’s obvious money and excitement on the table?

Building Wager was a way to see if I’d lean into “growth at all costs” or step back when it conflicted with what I claim to care about.

Spoiler: I did eventually step back. More on that later.

4. Key product idea: trust by default

Most existing platforms in this space share three problems we kept hearing from users and even from competitors during job-interview-style calls:

- Verification hell

Users have to upload screenshots, submit Twitch VODs, or argue in Discord whenever there’s a dispute. - Low trust

People believe “the house” or other players are cheating, and support teams burn time manually checking games. - Too many knobs

Bet on kills, assists, damage, placements, tournaments, side bets, jackpots… the complexity kills retention.

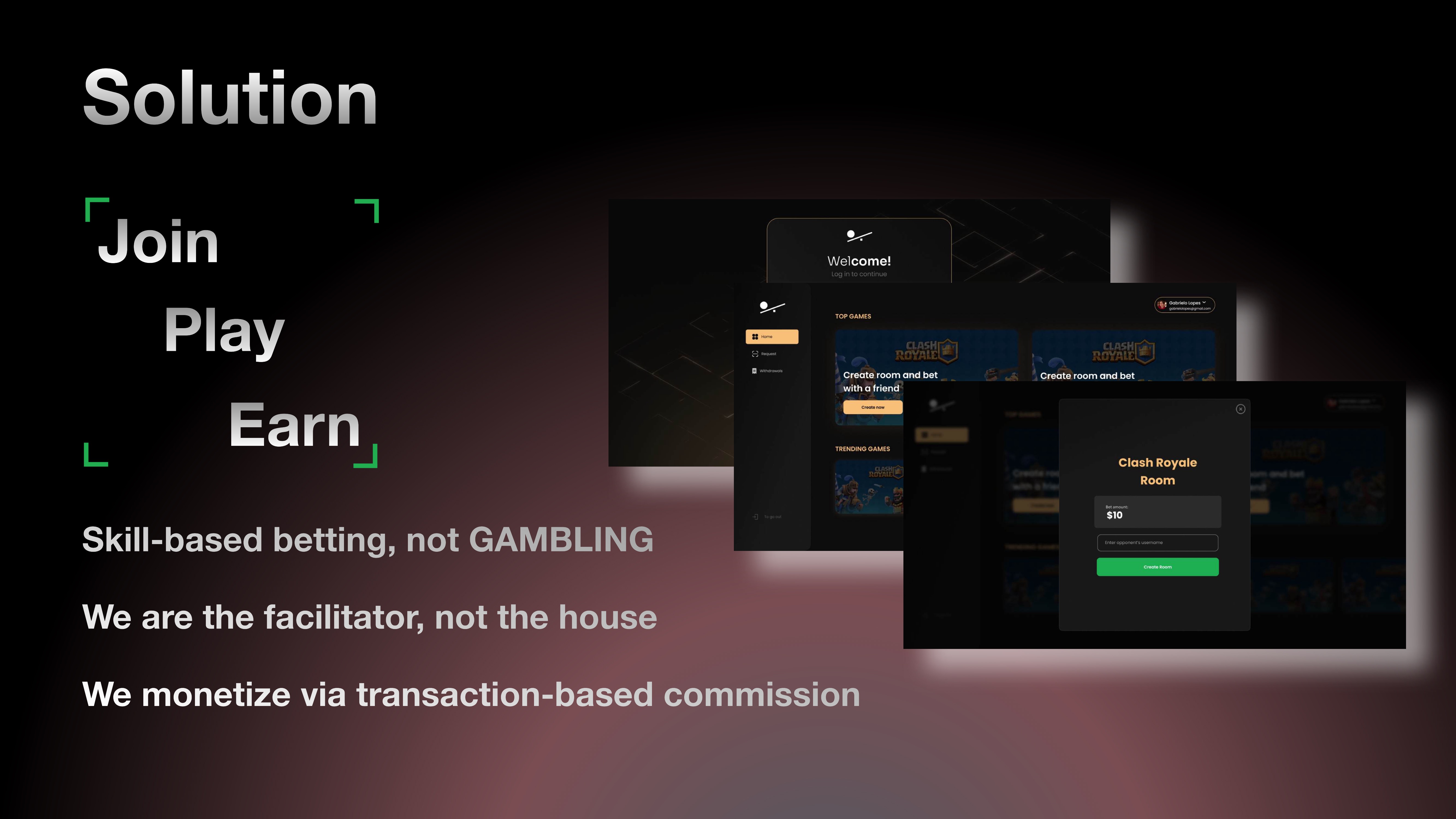

So we went the other way:

Our constraints

-

Only ship a game if we can verify results via API.

Clash Royale was ideal: you can fetch battle logs via official APIs and know exactly who won. Later candidates were games like Fall Guys with similar telemetry. -

Only one bet type: did you win or lose?

No complicated odds, no betting on others, no side markets. -

We’re the facilitator, not the house.

Two players stake money, winner gets the pot minus commission. The platform doesn’t bet against users.

This “trust-first” angle became our main differentiation and shaped everything from the backend to the UI copy.

5. How the MVP actually worked

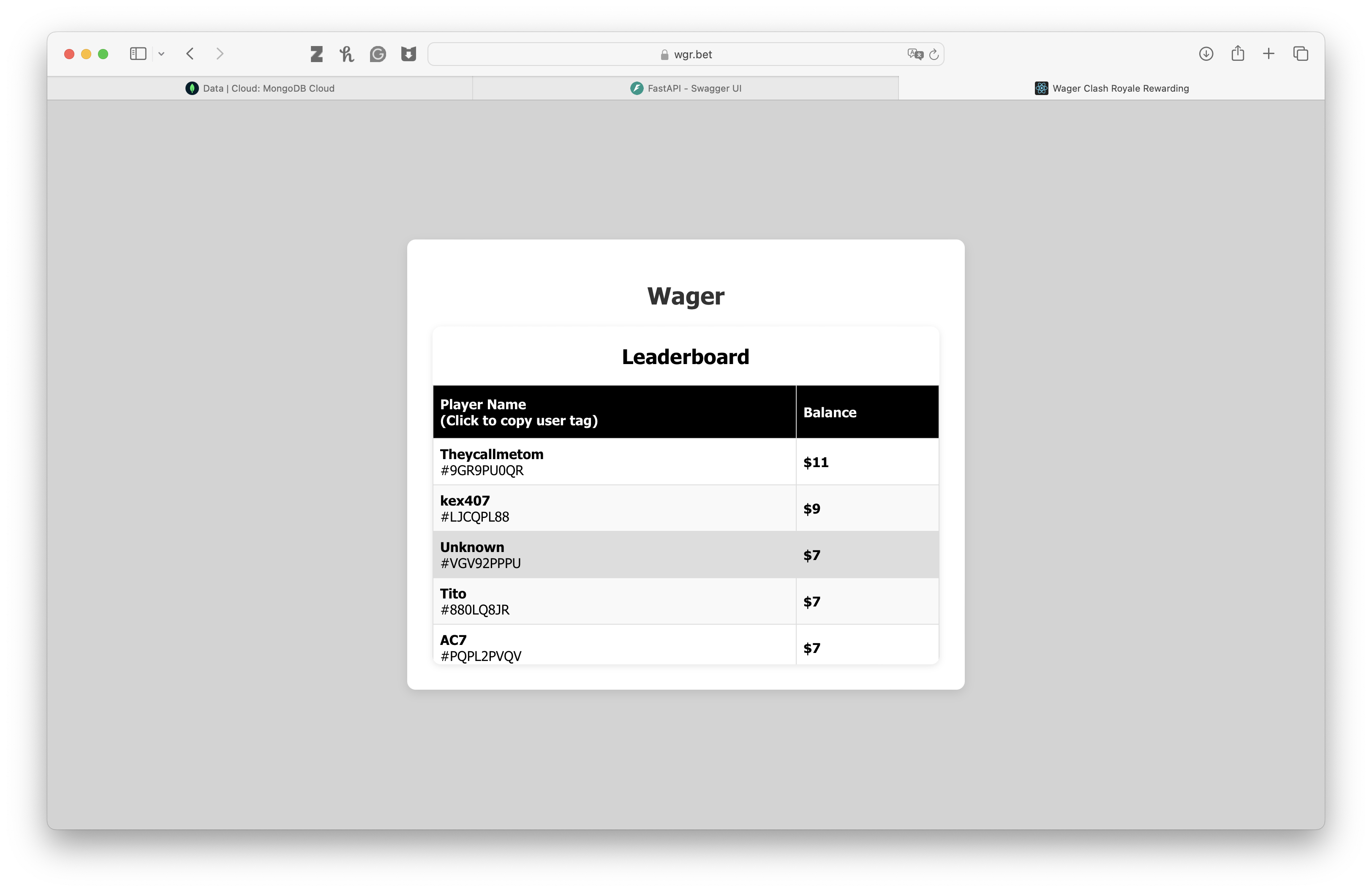

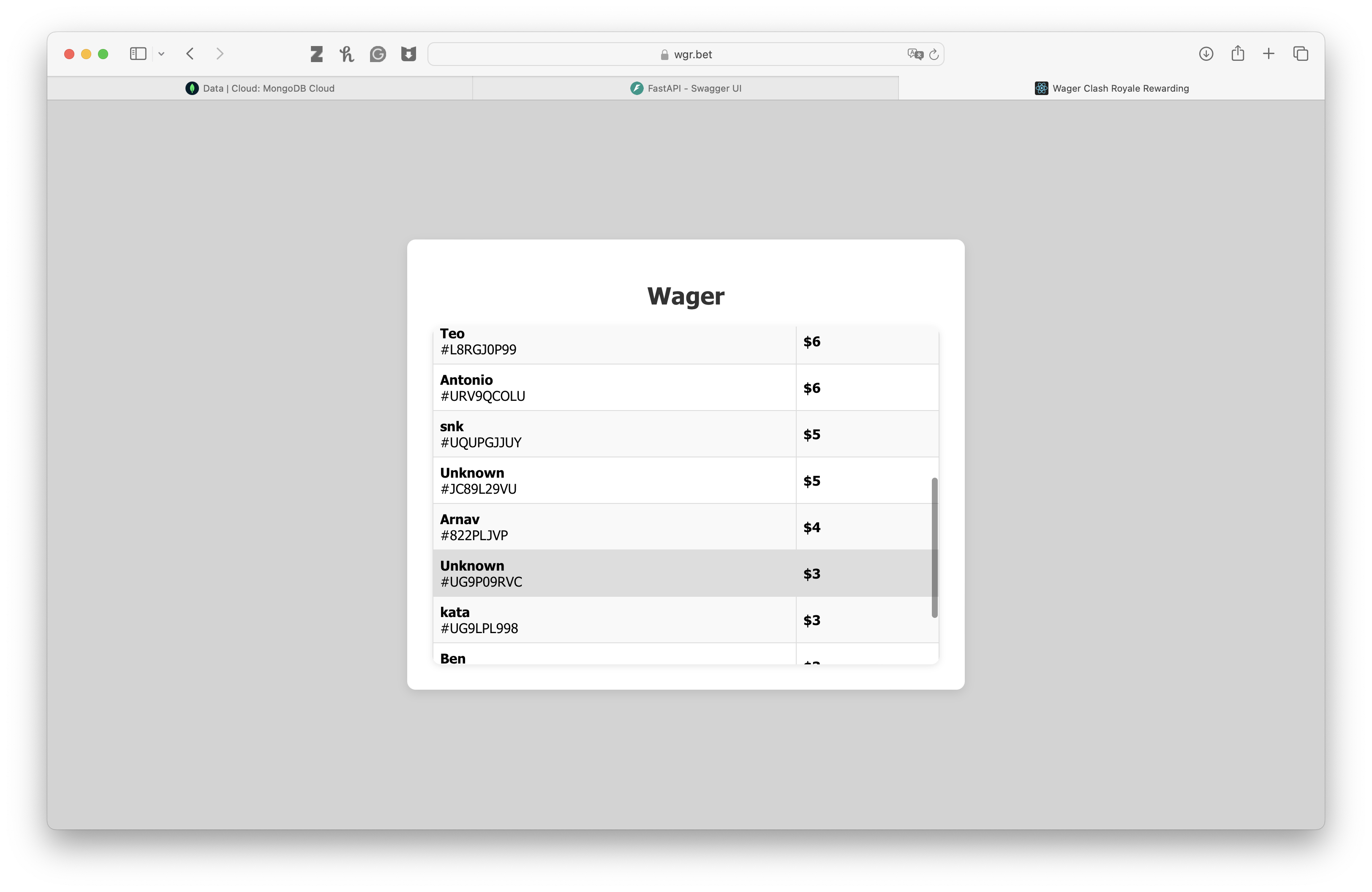

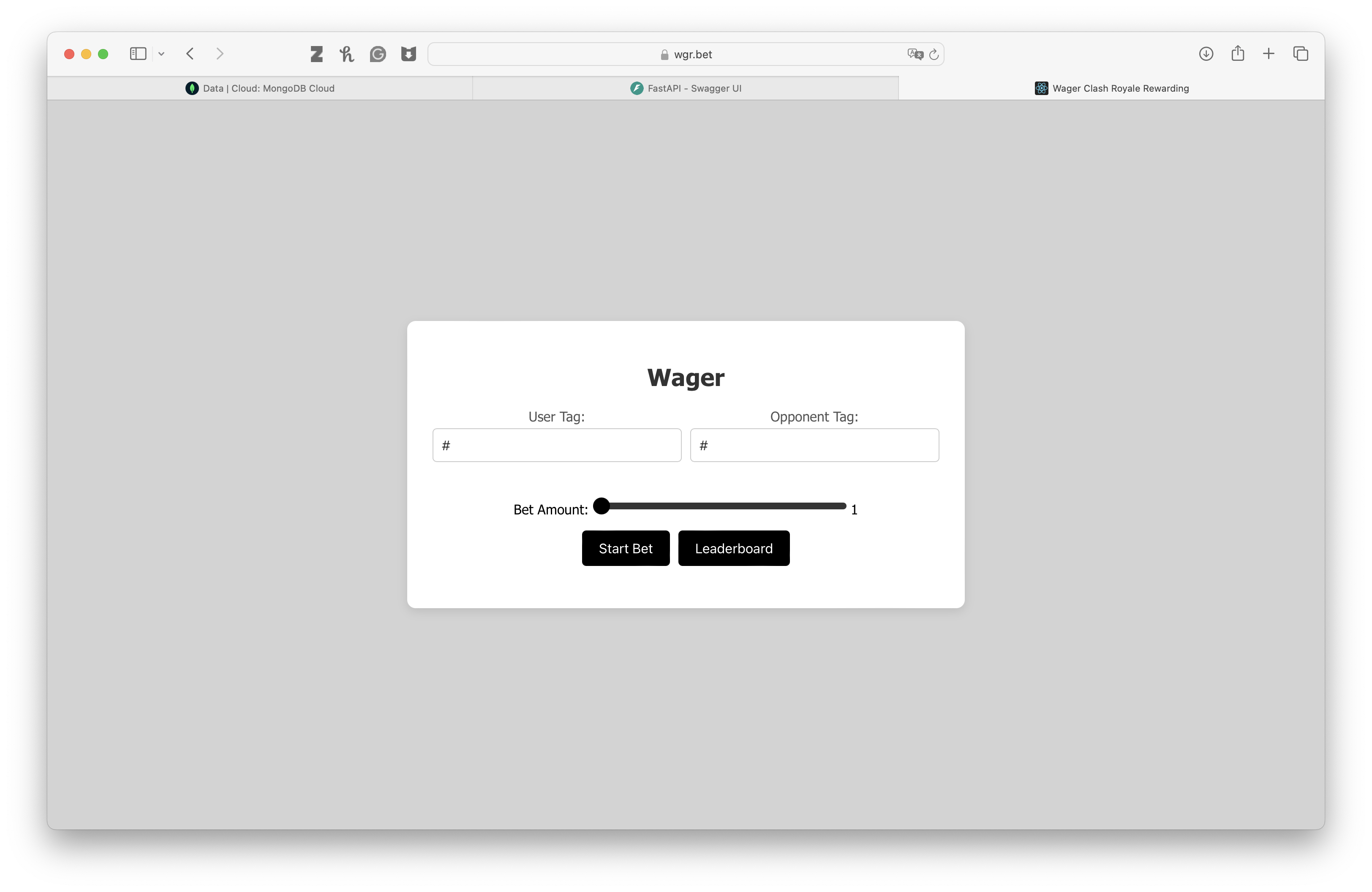

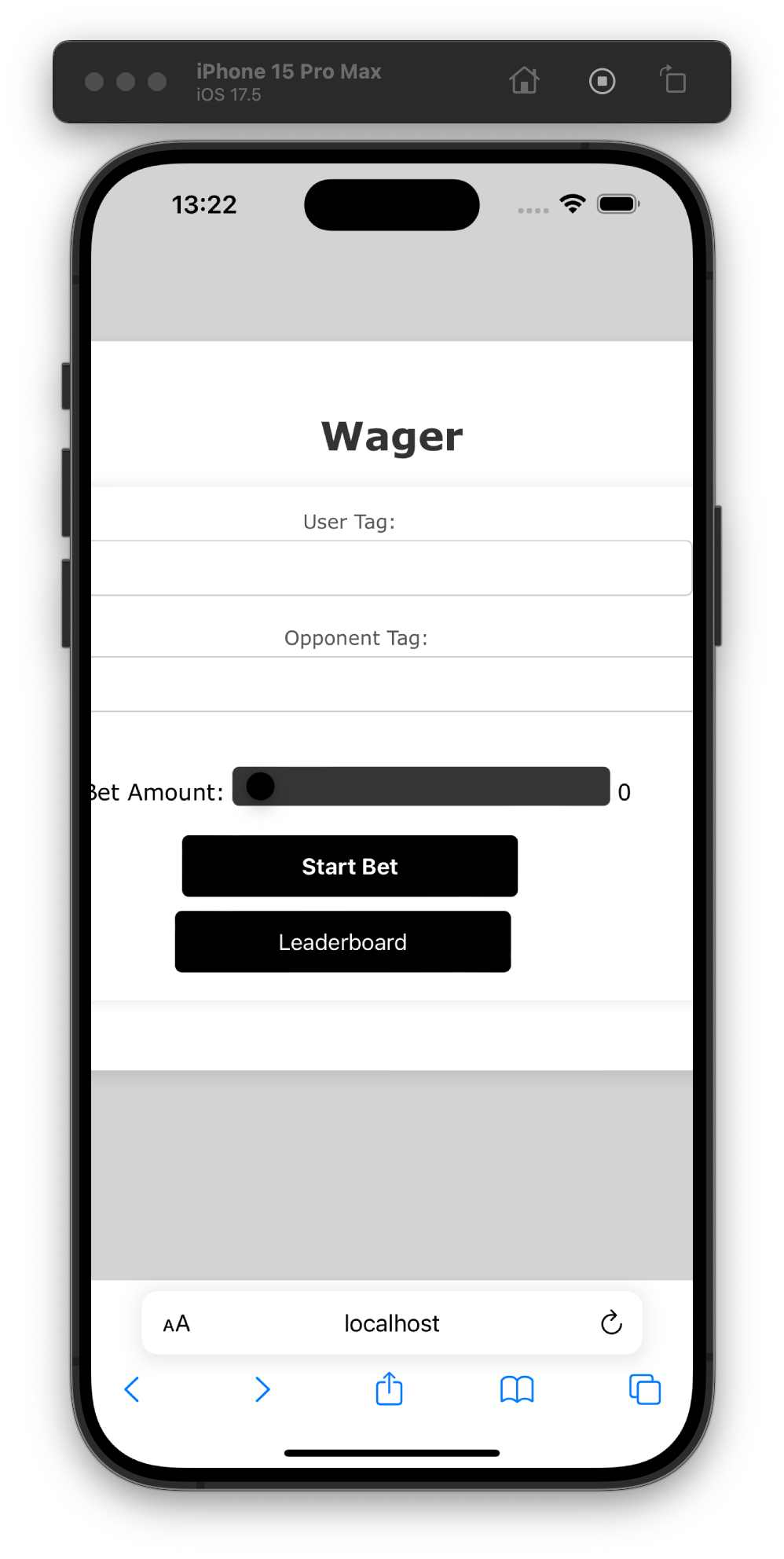

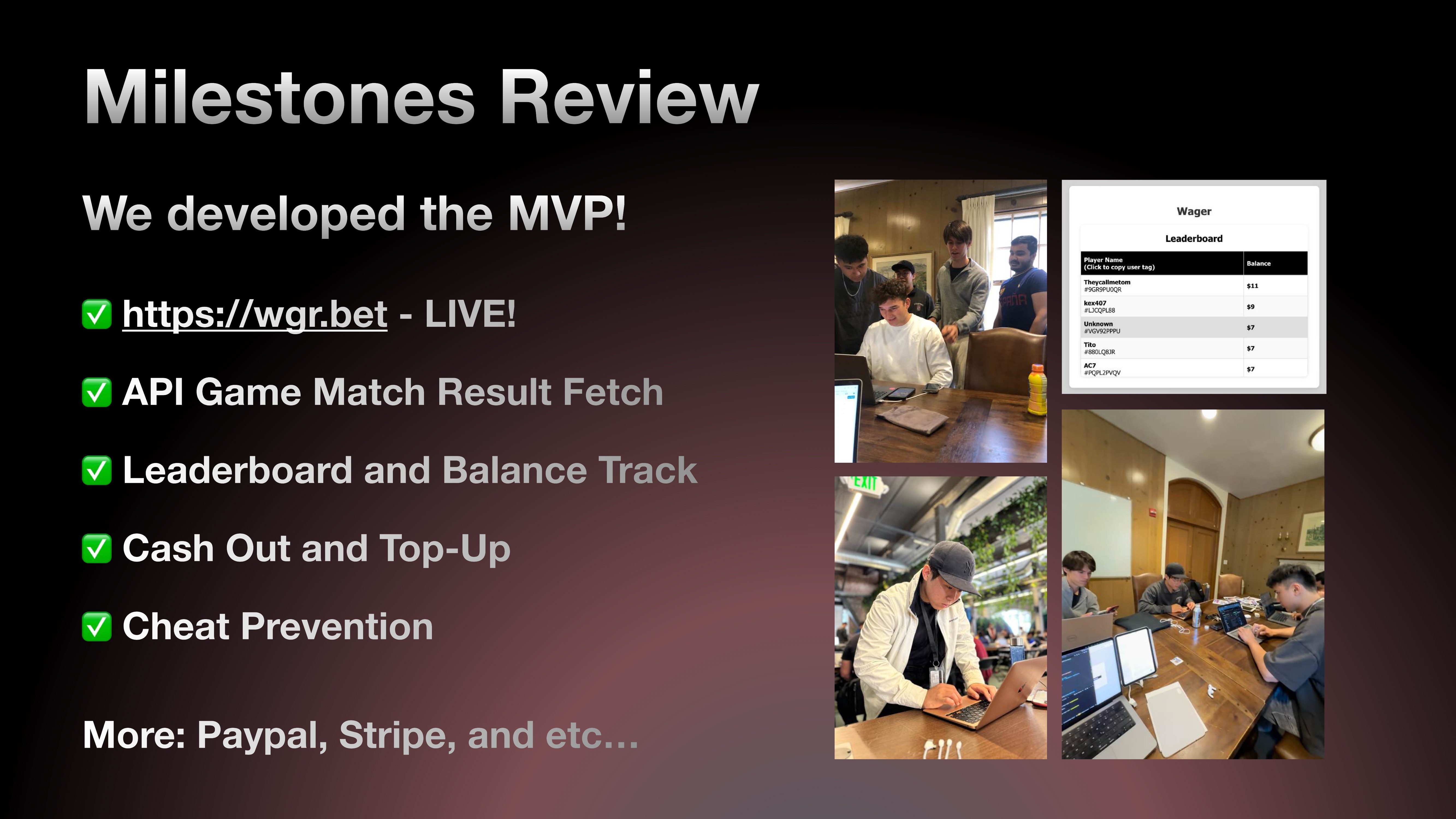

We built a simple web app at https://wgr.bet that connected directly to Clash Royale:

-

Identify players

- Each player pasted their Clash Royale user tag.

- We hit the Clash API, validated they existed, and either created or linked a Wager user.

-

Place a bet

- Both players agreed on an amount (we gave each new user $5 to play with at the event).

- Money stayed in an internal balance until cash-out.

-

Play the game

- Players started a friendly match in Clash Royale as usual.

-

Auto-verify the result

- Once the match ended, we fetched the latest battle log from the Clash API.

- The backend computed the winner and updated both balances in a single transaction.

-

Leaderboard for social pressure

- A simple leaderboard showed balances and win stats per user tag just enough to trigger rivalry.

Technically, the stack was:

- Backend: FastAPI + MongoDB on Google Cloud Run.

- Frontend: React web app.

- Infra: Containerized, minimal CI/CD, but robust enough to handle real money and API failures.

I owned the initial MVP end-to-end from API exploration to database schema and deployment then paired up with Shayan, our CIO, who rewrote key backend components and built the first proper React UI.

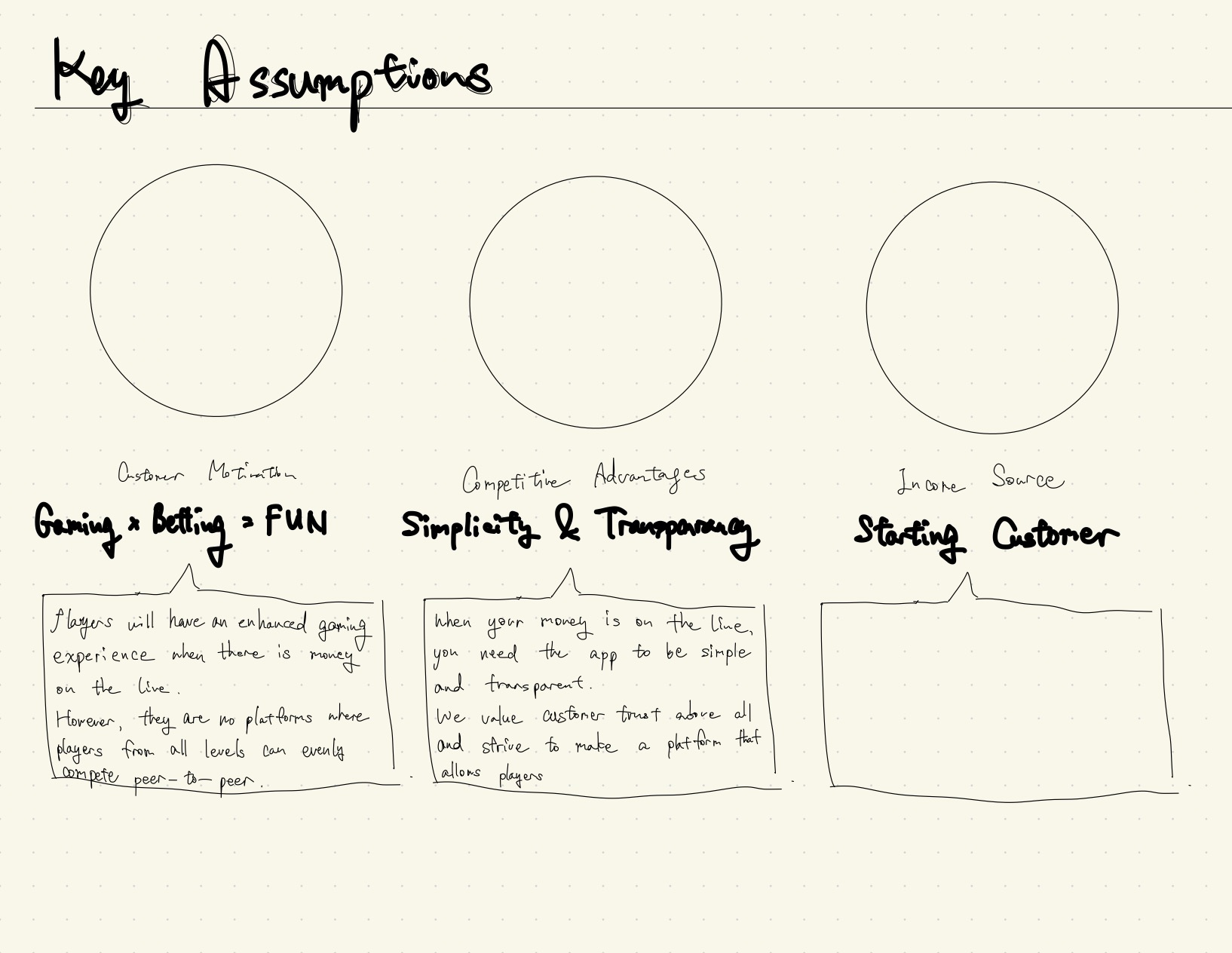

7. Showing the thinking

I like making my assumptions explicit, especially when I’m nervous about them.

We sketched three big pillars on paper before writing a line of code:

-

Gaming × Betting = FUN

Players will have an enhanced gaming experience when there is money on the line.

-

Simplicity & Transparency as competitive advantage

When your money is on the line, you need the app to be simple and transparent.

-

Starting with customers we know

College gamers like us are the easiest starting segment we understand their habits and group dynamics.

From there, the process artefacts looked like this:

8. Why it makes money (+ why that scares me a bit)

Financially, the logic is chillingly straightforward:

- Take the top ~15% of highly engaged viewers of something like the Esports Olympics (~30M expected viewers) and assume:

- 10 bets/week

- average $5 stake

- 10% commission

Even conservative penetration gives you nine-figure revenue potential.

At the micro level we saw the pattern immediately:

- Give each user $5 of “free” credit → they start playing “for fun”.

- Once they’re in, it becomes “I just need to win back to even”.

- The social layer (“you lost to Tom again?”) is a stronger retention driver than any push notification.

From a pure business perspective: it’s beautiful.

From a values perspective: it’s… worrying.

Wager showed me how easy it is to justify everything:

- “It’s skill, not luck.”

- “We cap stakes, we’re safer than casinos.”

- “We’re democratizing esports income for the 99.8% who aren’t pros.”

All of those statements are partly true and still, the machine we were designing monetizes tension, loss, and competitive ego.

That realization is a big reason I didn’t keep pushing Wager as my long-term company.

9. Outcome: handing the reins to someone else

By the end of the Stanford term:

- We had a working MVP, real users, revenue from commission, and a €100k term-sheet-style offer from Sukna Ventures.

- The team then scattered across four time zones (NYC, Berlin, Tokyo, Karachi). Coordination costs went up; momentum went down.

Eventually, the concept was spun out and picked up by Jack Mascone at Antler in New York, who is now taking it forward full-time. My role is best described as early co-founder and product/engineering lead on the first iteration.

Here’s the short team pitch we used to tell that story:

I’m still proud of the execution but I’m also comfortable that someone else is now the one optimizing conversion funnels in this space.

10. What I learned (about product and about myself)

On product & markets

-

Trust is the real feature.

In high-stakes spaces, users care more about clarity and fairness than about features. Our biggest differentiator wasn’t “betting on more games”, it was “automatic, uncheatable results.” -

Regulation is product surface area.

Payments, KYC, and platform policies are the product for anything touching money. Our payment provider research doc was as important as any Figma mockup. -

Narrow beats broad.

Focusing on just Clash Royale and a single bet type made it possible to get to a live test in weeks instead of months.

On my own values

-

I liked the craft of building Wager more than the idea of scaling it.

That’s a signal: I enjoy complex, slightly edgy systems as experiments but I don’t necessarily want to dedicate years to them. -

I’m happier working on products that compound value (like internal AI tools or education) than on ones that monetize impulses, even when they are “less bad” than the alternatives.

-

Saying “no” to continuing Wager as my main focus even with investor interest was a good test of whether my values are just marketing copy or actually guide my decisions.

6. The social experiment: a Stanford tournament

To test our assumptions, we hosted a Clash Royale tournament at Stanford:

The interesting part wasn’t the absolute numbers. It was behavior:

We watched:

The result: the energy in the room was fun, loud, and competitive but not (yet) dark. Still, you could feel how thin that line is.