ETH InCube x Roche 2025 – AI for Early Parkinson’s Detection

Two weeks of living and working in a glass cube with Roche & IQVIA to design responsible healthcare AI

Overview

InCube is ETH Zürich’s extreme design thinking & entrepreneurship lab:

5 cubes, each with 5 students, 5 days, 1 real-world challenge - all while living and working in a transparent 5x5m glass cube in the middle of major Swiss cities.

Our cube had a focus on the pharmaceutical industry and was sponsored by Roche & IQVIA with the brief:

“Decode Parkinson’s: how can AI turn complex, multi-modal data into clear, usable insights that support day-to-day care?”

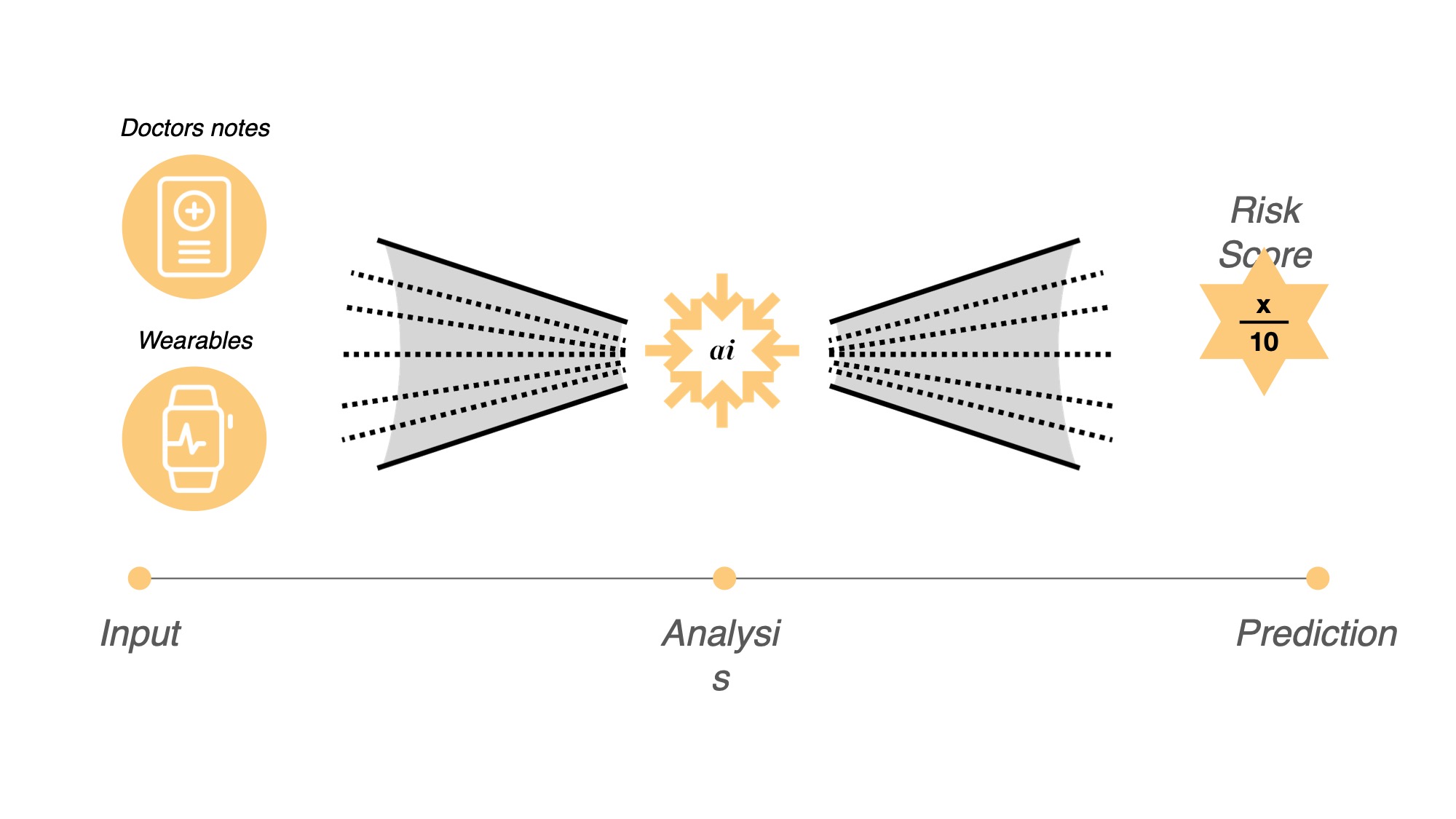

We called our solution Sentinels, an AI-supported system that helps doctors spot early signs of Parkinson’s before motor symptoms appear, by combining electronic health records with patient-owned data from wearables.

“Living, sleeping and building in a 5×5m cube for 5 days.”

The Challenge

Parkinson’s is often diagnosed years after the first symptoms appear. In practice:

- Early warning signs are subtle (sleep, smell, tiny motor changes).

- Data is scattered across dozens of touchpoints: GP visits, specialist notes, medication, wearables, patient diaries.

- Clinicians have 10-20 minutes per visit and are overwhelmed by documentation.

- Misdiagnosis and late diagnosis cost the system money - and patients, quality of life.

Our sponsor challenge framed this clearly:

“How might we use AI to decode Parkinson’s and support personalised, day-to-day care - without adding extra burden on clinicians?”

Constraints

- Must integrate into existing clinical workflows (Roche & IQVIA emphasised: “If it doesn’t work in the EHR, it doesn’t work at all.”)

- Must respect regulatory, privacy and data-protection requirements.

- Must create value for patients, clinicians, payers and researchers, not just one of them.

Where Parkinson’s gets lost today:

Clinitians and doctors on average see up to 40 patients per day, which is a lot of data to process and forget.

We spoke to a patient who had been diagnosed with Parkinson’s with only age 30 after 5 years of symptoms. She had been to the doctor multiple times, but both doctor and patient never could have predicted that she would be diagnosed with Parkinson’s at such a young age. This patient was perscribed yoga and mindfulness exercises. But only after trying levodopa and deep brain stimulation she finally got some relief.

This is a common story, as Parkinson’s is often diagnosed years after the first symptoms appear. When the first symptoms appear, already 50% of the dopamine neurons are lost.

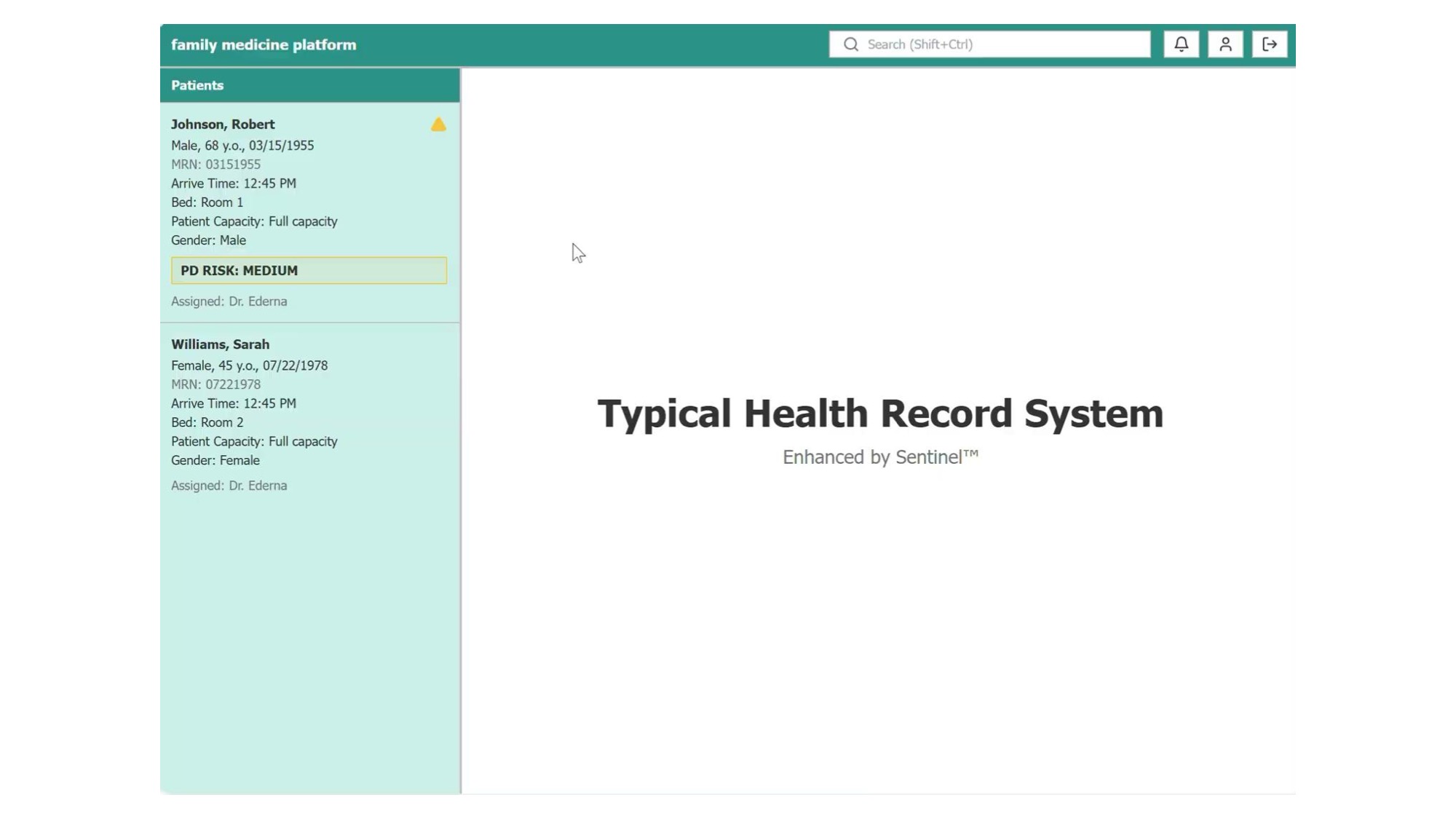

Health record systems could have prevented this misdiagnosis. However, they lack a clear overview and context, making it difficult to spot early signs of any disease just by looking at the data. Also hospitals keep their data siloed, making it difficult to share data between different systems. Patients don’t have access to their own data and have to rely on the doctor to tell them what’s going on.

This is what a typical health record system looks like:

Team & Setup

Our cube team was preassigned at the end of the first week in Davos. We were a team of 5 + 1, combined medicine, biotech, AI and design:

- Ghassan Abboud – Biomedical Engineering

- Nuno Rua – Doctor of Medicine

- Manushi Khatlawala – Design Researcher & Marketing

- Zeynep Savaseri – Health Sciences & Technology

- Me (Maximilian Arnold) – AI, InteractionDesign & Software Engineering

- Nastazja Monika Graff – Roche Cube Facilitator (former InCube winner)

On the sponsor side, we had ongoing feedback from Roche experts and IQVIA data scientists, who stress-tested everything from clinical validity to data access and business model. We also were able to conduct interviews with patients, doctors, foundations and other stakeholders to get a better understanding of the problem and the context.

Process - From Davos to Basel

We had two intense weeks:

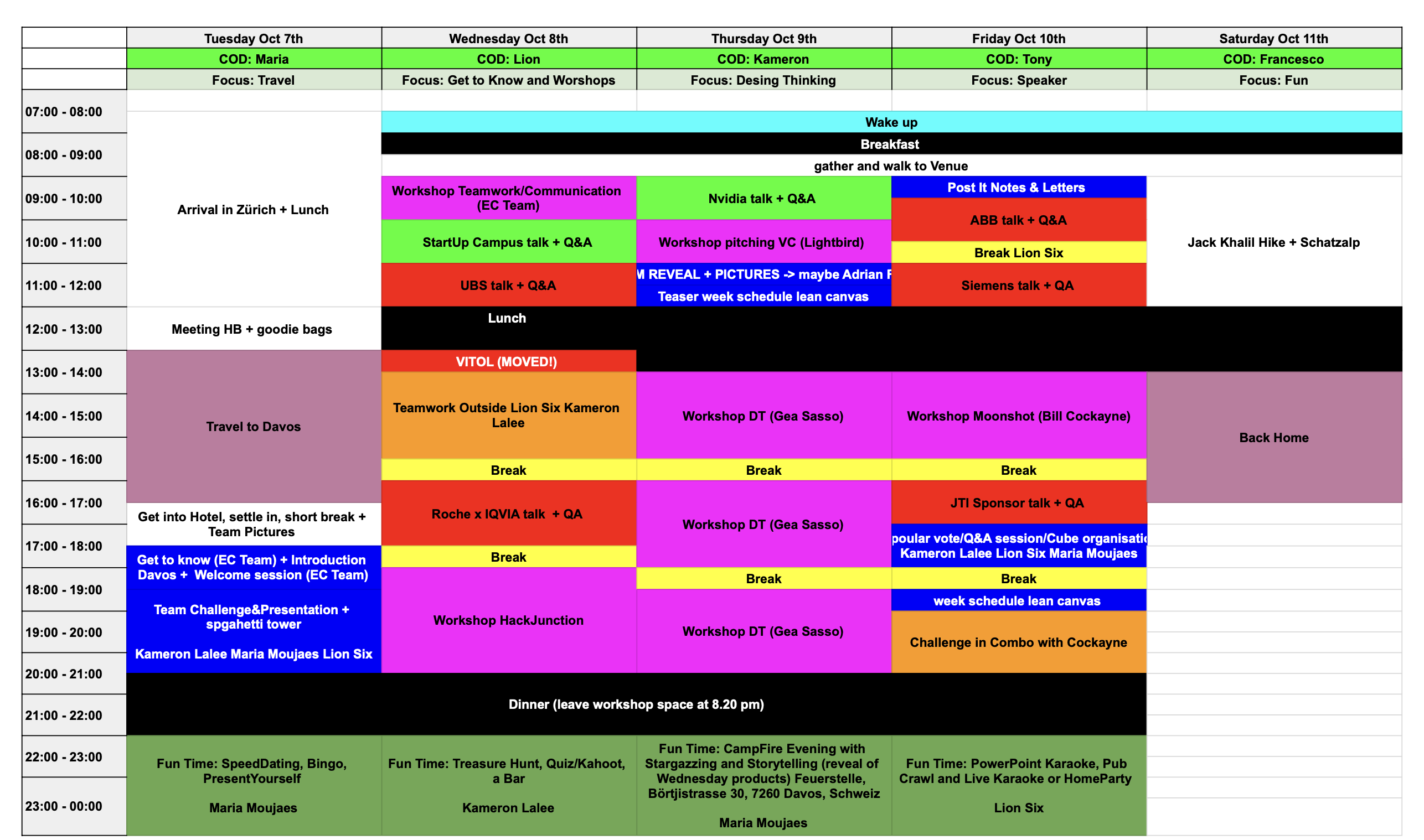

1. Prep Week in Davos - Framing & Foundations

Part of preparing for the cube, was getting to know the group of 30 participants prior to forming the teams. After everybody had arrived in Switzerland, we left off to Davos for a week of intense workshops covering topics from AI to design thinking to Moonshot thinking and venture capital.

We had industry experts from Stanford, HSG, NVIDIA, Lightbird VC, Roche, Siemens, ABB and others teaching us in interactive sessions.

This definitely meant a lack of sleep:

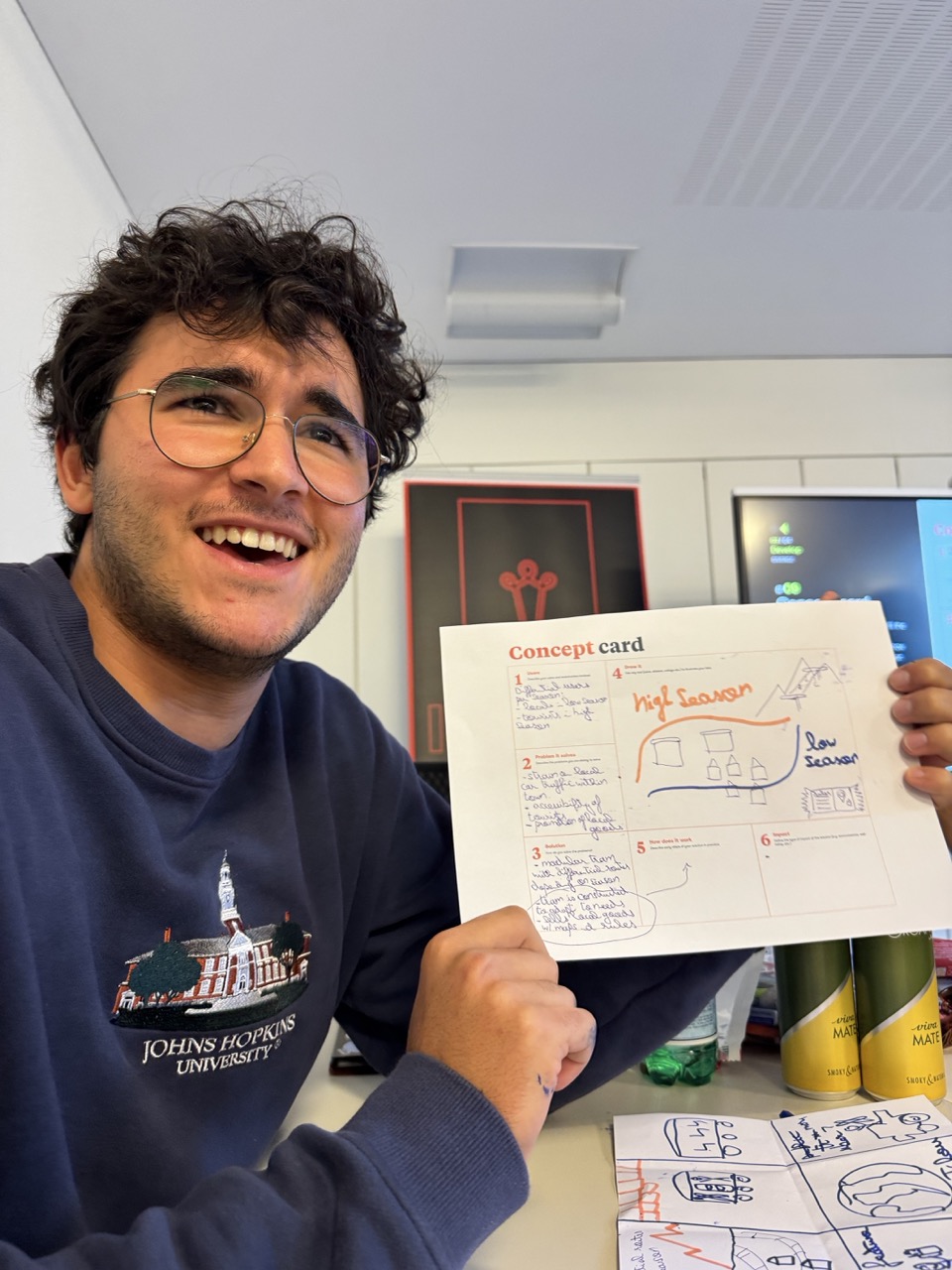

Here are some impressions from the week:

One of the many challenges: Build a device that can drop an egg from a height of 10 meters without breaking it.

Finally after one week of intense workshops, lot’s of Redbull, student food and short nights, we were assigned into our teams:

2. Moving into the cube: Day 1-2 in the Cube - Problem Shaping

Entering the cube

We entered the glass cube in Solitude Park at Roche’s Basel campus and immediately were confronted with the challenge:

Framing the problem together

- Clarified the clinical landscape of Parkinson’s (current guidelines, diagnostic pathways, ongoing drug trials).

- Ran structured team-building exercises to understand each other’s strengths and working styles.

- Sketched first versions of:

- A patient journey from first symptoms to diagnosis.

- A systems map of stakeholders (patients, neurologists, general practitioners, insurers, pharma, regulators).

My focus: I pushed us to make patient stories concrete early. Moving from “Parkinson’s patients” to specific personas and decision points in the journey.

After the first day, we had a clear understanding of the problem and the context. We were able to start working on the solution:

- Reframed the brief from “AI for Parkinson’s” to

“Help doctors notice what would otherwise be missed.”

- Conducted expert interviews with Roche neurologists and IQVIA data leads:

- Where do they currently feel blind?

- What data is theoretically available vs. actually used?

- Identified two key decisions:

- “Should I investigate Parkinson’s now?”

- “Is this patient’s condition slowly changing?”

We sketched multiple concepts on the cube walls, including:

- A patient-facing app only.

- A research-only tool for trial recruitment.

- A hybrid clinician assistant.

- An AI wearable tracking patiets for visual biomarkers beyond the traditional ones like step count, heart rate and sleep.

By the end of Day 2 we committed to the hybrid approach.

User & System Insights

1. Fragmented data ≠ useful insight

We mapped all possible data sources:

- Electronic health records (diagnoses, medications, lab tests).

- Specialist notes and GP visits.

- Wearables (step count, tremor, sleep, heart rate).

- Patient-reported outcomes, diaries and caregiver notes.

Insight: Clinicians don’t want more data - they want less, but better curated. Time-poor doctors need a starting point for where to look, not another dashboard.

2. Doctors want support, not replacement

From discussions with Roche clinicians:

- They were open to AI risk scores, but only if:

- They could see what drove the score.

- It fit seamlessly into the existing EHR.

- “Black box” diagnostics were immediately flagged as unacceptable for high-stakes decisions.

We translated this into a principle:

Augment, don’t automate. Sentinels should highlight patterns and questions, not deliver a verdict.

3. Patients fear both uncertainty and over-surveillance

Patients and caregivers (via secondary research & Roche insights) expressed:

- Anxiety from not knowing what’s coming.

- Reluctance to be constantly monitored or labelled “at risk” without clear action.

So we designed the patient side to focus on:

- Tracking what matters to them (daily function, sleep, mood).

- Actionable conversations, not raw scores (“Here are 3 changes you might want to mention to your doctor”).

3. Day 3 - Prototyping Workflows & Data Flows

Naming the solution

Overnight we came up with a name for our solution: Sentinels.

Mapping doctor and patient workflows

We mapped Sentinels across two interfaces:

- Doctor view inside the EHR:

- Risk trending over time.

- Highlighted events from health records and wearables.

- Suggested next steps (tests, referrals, questions to ask).

- Patient companion:

- Lightweight, structured daily check-ins (sleep, mobility, mood).

- Integration with approved wearables / existing apps.

Prototyping the experience

We prototyped in Figma, with click-through screens for:

- Pre-consultation summary view for Monica (our fictional doctor).

- In-consultation conversation prompts.

- Post-visit recap for the patient.

The Sentinels Concept

What Sentinels does

Sentinels is an AI-supported system that:

-

Aggregates data

- Pulls structured data from EHRs (ICD codes, prescriptions, visit notes).

- Connects to approved wearables and patient-reported outcomes.

-

Generates an interpretable risk trend

- Produces a Parkinson’s risk trajectory over time instead of a single static score.

- Highlights which signals contributed most (sleep disturbances, smell tests, medication patterns, micro-motor changes).

-

Surfaces meaningful prompts

Instead of saying “This patient has Parkinson’s”, Sentinels suggests:

- “Sleep quality has worsened gradually over 18 months.”

- “Olfactory test deteriorated between visit A and B.”

- “Fine motor tests show a subtle trend worth follow-up.”

These appear as conversation prompts in the pre-visit summary, helping Monica decide:

- Do I bring up Parkinson’s now?

- Do I refer to a neurologist?

- Which tests or questionnaires should I run?

Interfaces

Doctor View (EHR plugin)

- A side-panel in the existing clinical system.

- Shows:

- Risk trend graph (with confidence intervals).

- Top contributing factors with short explanations.

- Suggested actions (order test X, ask question Y, consider referral).

Patient Companion

- Opt-in mobile interface focused on:

- 30-60 second daily check-ins.

- Passive wearable data (if available).

- Clear explanations: “Your data helps your doctor see patterns earlier - you stay in control.”

Design Principles

We surfaced four guiding principles on the cube wall and checked every design decision against them:

-

Human in the loop, by design.

No autonomous diagnosis. Doctors stay the decision-makers. -

Explainability over perfection.

A “good enough but interpretable” model beats a marginally better black box. -

Clinical first, not consumer gadget.

Success is measured by better consultations, not app usage stats. -

Incremental adoption.

Start with observational use (no clinical impact) and move gradually towards decision support once validated.

My role: translating these principles into concrete UX decisions - what we show, in what order, with what copy and level of detail - while working closely with our AI team members on what is technically realistic.

4. Day 4 - Business Model & Clinical Viability

Stress-testing viability

Together with Roche & IQVIA mentors we challenged the concept on:

-

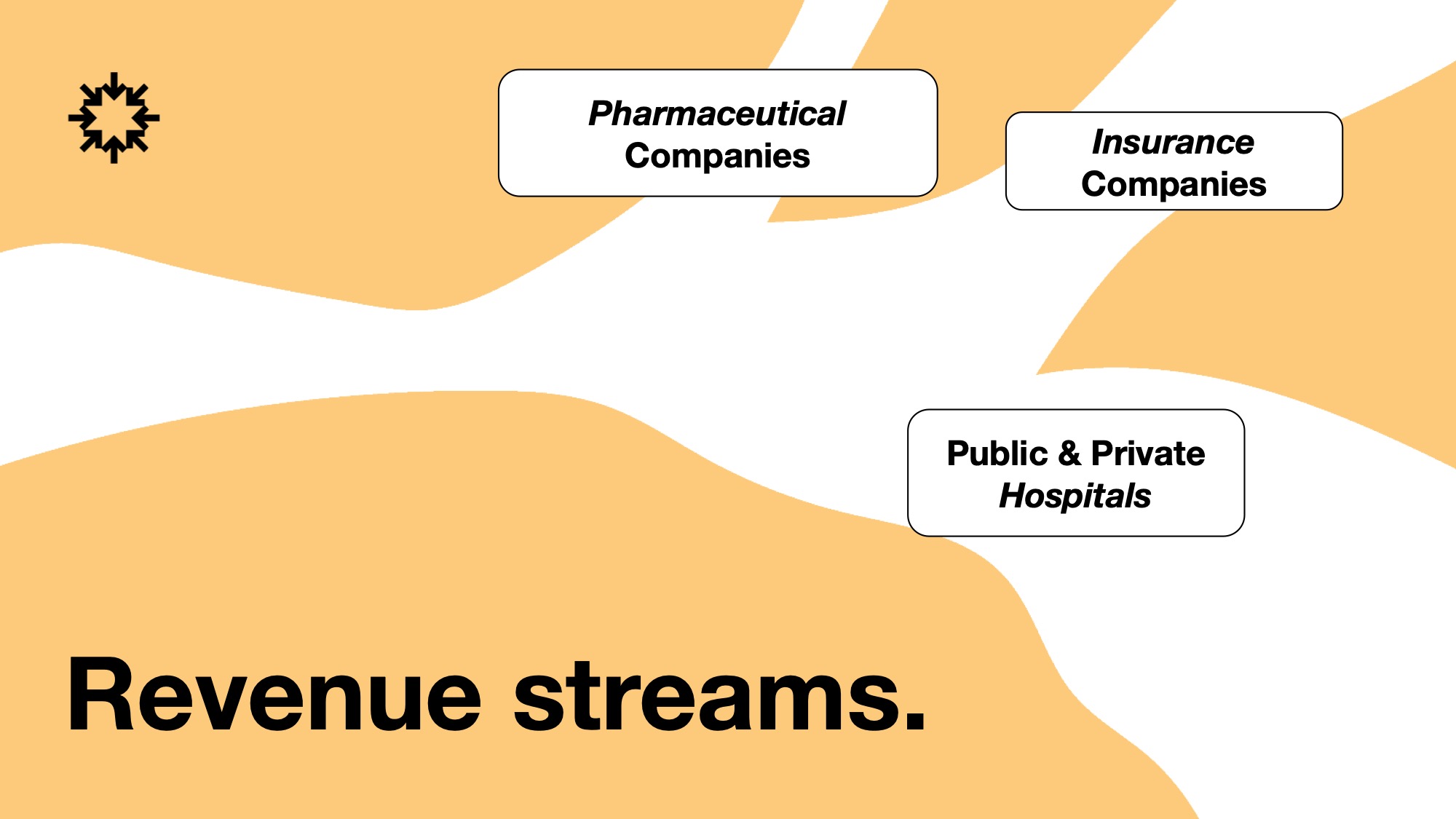

Who pays? – Payers and pharma, via:

- Reduced misdiagnosis and unnecessary visits.

- Better recruitment of early-stage patients into clinical trials.

Revenue Streams

-

Adoption path:

- Start as a clinical-decision support add-on for a limited set of neurology centres.

- Validate in observational studies before any claims about diagnosis.

Adoption Path

-

Regulatory strategy:

- Frame as a SaMD decision support tool, not an autonomous diagnostic.

Regulatory Strategy

- Frame as a SaMD decision support tool, not an autonomous diagnostic.

5. Day 5 - Storytelling & Pitch

Warming up for the final

Before the traveling back to Zurich, we had to submit a short summary of our solution to the jury. To prepare we had a quick stretching session:

We turned everything into a 3-minute pitch built around one story:

Monica, a clinical neurologist seeing 40+ patients per day, missing early signs of Parkinson’s because there’s simply too much fragmented information.

My role in the final pitch

My contributions here:

- Structured the narrative arc (problem → stakes → insight → product → business).

- Built the final pitch deck and live demo flow.

- Filmed and edited the final pitch and demo within 1 hour.

Turn on sound to hear the pitch and see the demo:

Impact & Awards

By the end of the week we had:

- A clickable prototype for both doctor and patient flows.

- A clear business model:

- Subscription model for clinics and hospital groups.

- Partnerships with insurers and pharma for early-stage recruitment into clinical trials.

- An adoption roadmap and first validation studies outlined with Roche & IQVIA mentors.

After these two intense weeks we were able to present our solution to the jury and the audience. And we won the Audience Award! 🎉

- 🏆 Audience Award at the 2025 InCube Challenge final, competing against teams sponsored by Siemens, ABB, UBS, JTI and Vitol.

- 💰 CHF 1,500 prize money for our cube.

- 🥇 Personal recognition: “Most likely to found a unicorn startup” award by my fellow cubees back in Davos.

Reflection - What I Took Away

1. Real impact requires cross-disciplinary humility

Designing for Parkinson’s care humbled me. My biggest contribution wasn’t a flashy interface, but:

- Asking naïve questions in clinical discussions and translating jargon into user needs.

- Helping align doctors, data scientists and designers around one clear decision we want to support.

2. Responsible healthcare AI is mostly about boundaries

The hardest (and most important) conversations were about what Sentinels shouldn’t do:

- We resisted the temptation to claim diagnostic capabilities we couldn’t safely back up.

- We intentionally scoped Sentinels as a decision support system, not a diagnostic tool.

This experience sharpened my thinking around safety, explainability and regulation in AI-driven products.

3. Living in a glass cube changes how you build

Working, sleeping and being visible 24/7:

- Forces radical transparency in how you collaborate.

- Made me aware I might want to chose who I live with carefully.

- Compresses feedback loops. Mentors, Roche employees and even passers-by could comment on our work through the glass.

- Made me more comfortable with sharing messy work in public and iterating quickly.

How this connects to my broader work

Sentinels sits at the intersection I care about most:

AI, complex socio-technical systems and long-term human wellbeing.

It strengthened my conviction that the most interesting AI products are not magical black boxes, but carefully designed tools that slot into existing human workflows and make them meaningfully better.